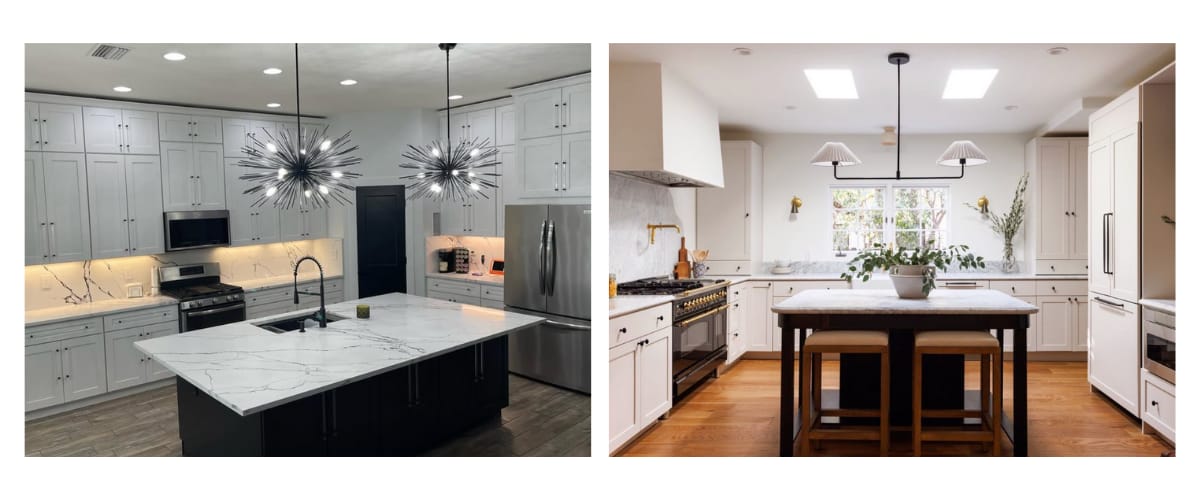

Over the (US Thanksgiving) holiday break, I spent a lot of time with my two amazing sisters, who both have impeccable and entirely different tastes…in almost everything. While hanging out in Florida with my sister-in-law, Brittany, I noticed how her taste (in interior design) leaned more toward ultra modern, dominated by black and white with sharp lines, punctuated by organic forms that are also often black (or white). Though my personal taste, at least from the perspective of home decor, doesn’t skew ultra modern, upon entering Brittany’s well-designed home, I was immediately struck by how much I liked what she had designed and how comfortable I felt.

Conversely, upon arriving at my sister, Erin’s, house in LA, it was immediately obvious that while her taste leaned more toward warm, organic colors and shapes, and closer to a vintage meets midcentury modern vibe, it was no less or more inviting than Brittany’s home. In fact, it’s hard to say which one I like more.

What’s more, I can confirm that professional taste played a part in the interior design of both homes. While Brittany has designed a gajillion rooms, she also worked with her mother on her current home, who’s been a practicing professional interior designer in Florida for decades. Erin is also a practicing professional interior designer in LA, where she also flips high-end homes. So…at least in my mind, this is an apples-to-apples comparison.

In other words, both women have what many of us would call impeccable taste. And, no, this does not mean we all have the same taste, or would even like the design decisions Brittany and Erin have made. Rather, these are two clear examples of designers who have made decisions based on their own sense of taste, both of which have something to offer (almost) everyone.

As I zoomed out from both experiences, I decided it was high time I began to piece together what (I believe) actually defines taste, and…what it takes to refine one’s own taste.

Here’s what I think…

— Justin Lokitz

Design Deep Dive

How Taste Actually Works (and Why It Separates Good From Great)

Taste has always been one of the most misunderstood parts of creative work. We talk about it as if it’s a fixed trait…something you either have or don’t. It’s often whispered as something magical and unattainable.

The mythical “good taste” person shows up fully formed, choosing the right fixtures or typeface on instinct, spotting the off-note in a composition before anyone else, or buying furniture that somehow makes a room feel intentional. But that framing creates a false hierarchy. Taste isn’t a talent. Taste is a practiced discipline. It’s a set of choices shaped by exposure, curiosity, lived experience, and the rigor to notice what’s actually going on beneath the surface.

If anything, my sisters reminded me that taste is about coherence and NOT having the same preferences. Brittany’s sharp contrasts and monochrome palette work because she commits. I saw this play out from the living room to the adjoining bathrooms and even outside. Erin’s mix of vintage warmth works because she edits (and curates) with care. Their homes aren’t good because they align with some standard. They’re good because they reflect an internal logic…and that logic is the real engine of taste.

A tale of taste…in two kitchens

In design, we talk a lot about intuition. Intuition is often just the shorthand for a trained eye. It’s the accumulated memory of patterns you’ve absorbed, evaluated, and filed away. As Michael (Ridd) Riddering states in this YouTube video about his own taste, “Taste is understanding what you think should exist, and then being able to repeatedly answer why.”

When I interview people on Design Shift, this idea shows up again and again. Maya Elise Joseph-Goteiner talked about how working across dozens of Area 120 products sharpened her judgment about what mattered and what was noise. She didn’t call that taste, but that’s what it was: a refined ability to distinguish the signal from the clutter.

Taste emerges from immersion. Designers who spend years in the craft build a library of references—visual, functional, even emotional—that guides their decisions. But taste can also stagnate if you never update that library. This is one reason why so many mid-career designers feel stuck. They’re still referencing the same aesthetic and conceptual models they leaned on fifteen years ago. Meanwhile, the world has shifted under their feet.

I’ve written before about this: how designers must become leaders in an age of AI, not by clinging to nostalgia but by interpreting new patterns and shaping meaning from them. Good taste is the unglamorous foundation of that work. It’s what helps you filter the endless stream of new tools, trends, and technologies and decide what deserves your attention. Taste protects you from chasing novelty for novelty’s sake. It turns the infinite scroll of options into something navigable.

Taste also has a moral dimension. When you decide what’s good and what’s not, you’re making a judgment about what’s worth amplifying. You’re shaping culture, even in small ways. That’s true for a designer picking a color system, a founder choosing what to prototype, or a leader deciding how a team makes decisions. Taste isn’t just about how something looks. It’s about what it says and what it does.

So where does taste actually come from? Well…at least from my experience, taste comes from (at least) three places.

The first is exposure.

You need to see enough variation to notice differences. My sisters (and Brittany’s mom) didn’t end up with coherent taste because they stumbled into it. They both immerse themselves in their domains, constantly collecting references and textures and ideas. For instance, the marble backsplash in Erin’s kitchen has a thin line of beautiful inlaid brass. A detail I had never seen. When I asked her about it, she replied that she “stole the idea” from handmade furniture, where you often see inlay details. Designers across other domains are no different. If you only look at the same 20 Dribbble shots or the same two design systems, your taste will narrow until it becomes brittle. Broader exposure increases the resolution at which you notice quality.

The second is reflection.

Exposure alone isn’t enough. Recalling Ridd’s earlier quote, you must interrogate why something resonates, and “repeatedly answer why”. What’s the underlying structure? What’s the decision behind the decision? This is where most people fall short. They consume but don’t process. They notice but don’t dissect. In past articles and interviews, I’ve highlighted designers like Chris Basey and Stephanie Knabe not because they simply produce good work, but because they have frameworks for understanding why their choices work and how they guide others to make better decisions. Reflection turns taste into a transferable skill.

The third is iteration.

Taste refinements happen through action, through the countless times you pick between two imperfect options and pay attention to what feels off. One of the fastest ways to improve your taste is to make more things and study why they fail. Bad work isn’t a liability. It’s an archive. Everything is a prototype, after all. Every version you dislike teaches you something about your standards. Over time, those standards sharpen into principles. Principles then shape every choice you make.

This leads to the question I hear from students and clients all the time: Can you teach taste? The short answer is yes. The longer answer is that you don’t teach taste by telling someone what’s good. You teach it by showing them how to see.

In workshops, I’ll often ask a team to deconstruct examples of work they admire. Not the aesthetics, but the logic. Why does this design feel calm? Why does that interface feel trustworthy? What choices reinforce that? What choices contradict it? Once someone learns to name the mechanics behind an experience, they begin to build their own sense of judgment. You can accelerate this process by giving people constraints that force tradeoffs. Taste develops fastest when you can’t rely on quantity to hide poor quality.

Another underrated move is teaching people to build personal libraries. This can be everything from Pinterest boards to more holistic collections of work that represent the edges of what they find compelling. Not perfect work, but provocative work. When someone maps the boundaries of their fascination, they develop a clearer sense of what feels aligned and what feels off. Over time, those boundaries evolve. That evolution is the refinement.

Leaders who want to help others grow their taste should practice something few of us enjoy: narrating our internal decision-making, in a way that reveals the pattern recognition behind our choices. This is hard because experienced designers often compress years of logic into a sentence like “it just feels heavy.” That doesn’t help anyone. When you unpack your thinking—why the spacing threw off the tension, why the color choice flattened the hierarchy—you give others the tools to construct their own systems of judgment.

Taste also shapes how teams navigate ambiguity. When a team shares a common standard of quality, they move faster because they debate at the level of ideas rather than preferences. They understand what they’re optimizing for. They know when a direction feels promising and when it feels off. That’s one reason designers tend to excel in founder roles. They’ve spent their careers refining taste and applying it to messy situations where clarity isn’t handed to them. Maya talked about this in her interview: how designers are wired to work through uncertainty and still find form. Taste is part of that wiring.

But taste can also close you off if you’re not careful. The moment your taste becomes rigid, you stop seeing possibilities. You dismiss unfamiliar patterns. You assume your preferences are truths. Every great designer I know protects against this by deliberately seeking out work that challenges their instincts. They force themselves to sit with things they don’t immediately like and ask why other people find them compelling. They don’t abandon their standards. They pressure-test them. They ask why seven (or more) times.

As designers, we’re entering a period where the market is flooded with generative work. AI can produce a thousand variations of anything in seconds. That doesn’t make taste less important. It makes taste essential. If the baseline keeps rising, the differentiator won’t be who can create the most options. It’ll be who can recognize what’s meaningful. Taste becomes the filter.

So, how might someone (even you) refine their taste starting today?

Study more than you consume. Slow down enough to notice what’s actually happening in the work around you.

Reflect on why you like or dislike something, and capture that reasoning so it can evolve.

Make more things, even small things, and use the outcomes to update your standards.

Expose yourself to disciplines outside your own. Architecture, typography, cuisine, fashion, literature. Taste cross-pollinates.

Discuss work with others and stay open to being wrong.

And, most importantly, revisit your own assumptions on a regular basis. If your taste looks the same today as it did five years ago, that’s a sign you’re overdue for recalibration.

Both of my sisters have wildly different aesthetic sensibilities, yet both have refined them through years of attention, experimentation, and curiosity. That’s the blueprint for all of us. Taste isn’t an asset you inherit. It’s a muscle you train. And it becomes one of the most powerful tools you have—whatever you’re designing next.

Subscribe to Design Shift for more conversations that help creative professionals grow into strategic leaders.

This newsletter you couldn’t wait to open? It runs on beehiiv — the absolute best platform for email newsletters.

Our editor makes your content look like Picasso in the inbox. Your website? Beautiful and ready to capture subscribers on day one.

And when it’s time to monetize, you don’t need to duct-tape a dozen tools together. Paid subscriptions, referrals, and a (super easy-to-use) global ad network — it’s all built in.

beehiiv isn’t just the best choice. It’s the only choice that makes sense.

What did you think of this week's issue?