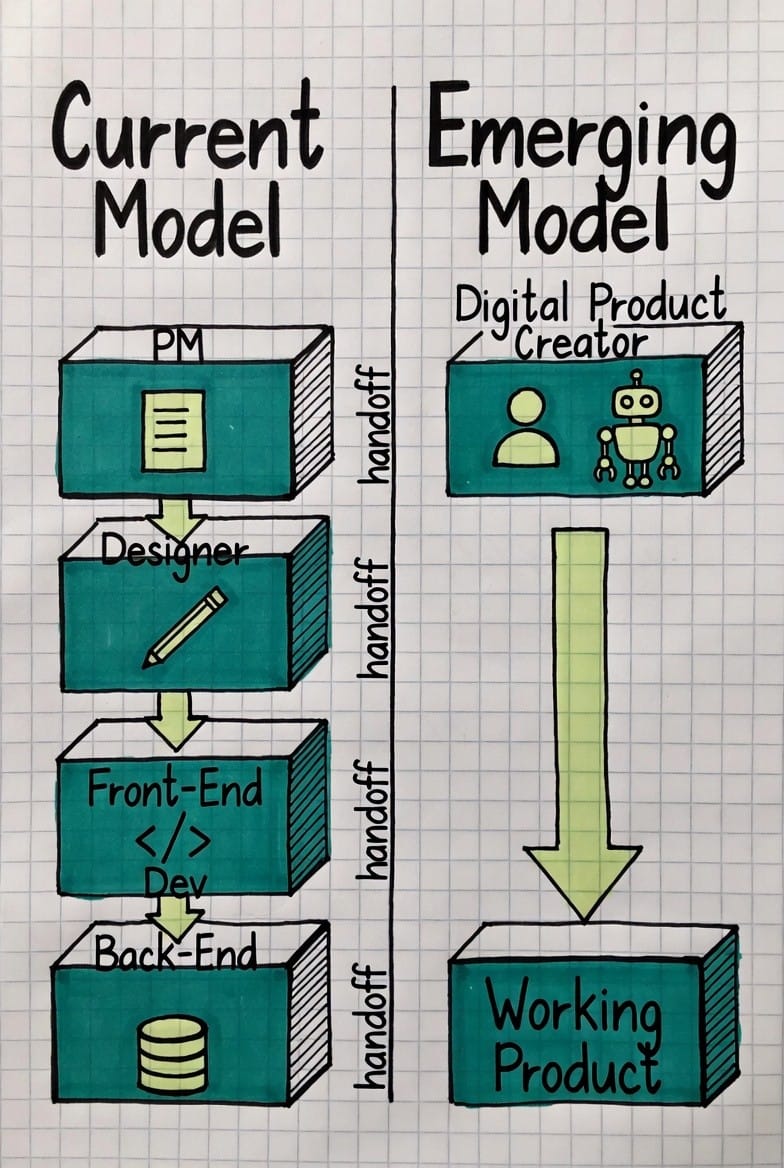

I've been thinking a lot about how with the advent of generative AI and vibe coding the roles of designer, product manager, and software engineer are beginning to compress or merge. As my good friend Sid Vanchinathan described in our interview and his LinkedIn article, how we used to create software…

Product manager to write requirements and manage the roadmap

Designer to figure out the user experience and interfaces

Front-end developer to build what users see

Back-end engineer to handle data, logic, and infrastructure

Months of coordination, handoffs, and iteration

...is merging into what he calls a digital product creator.

And…it’s not just Sid and me thinking this way. Just this week, Lenny Rachitsky had Marc Andreessen as a guest on his Lenny’s Podcast. Though they touched on lots of interesting tech-related topics, they spent much of the discussion talking about this very thing! Basically, AI in the hands of any one of these roles, especially when they're experts in their roles, makes them indispensable. What's more, anyone who becomes knowledgable in more than one role, becomes exponentially indispensable.

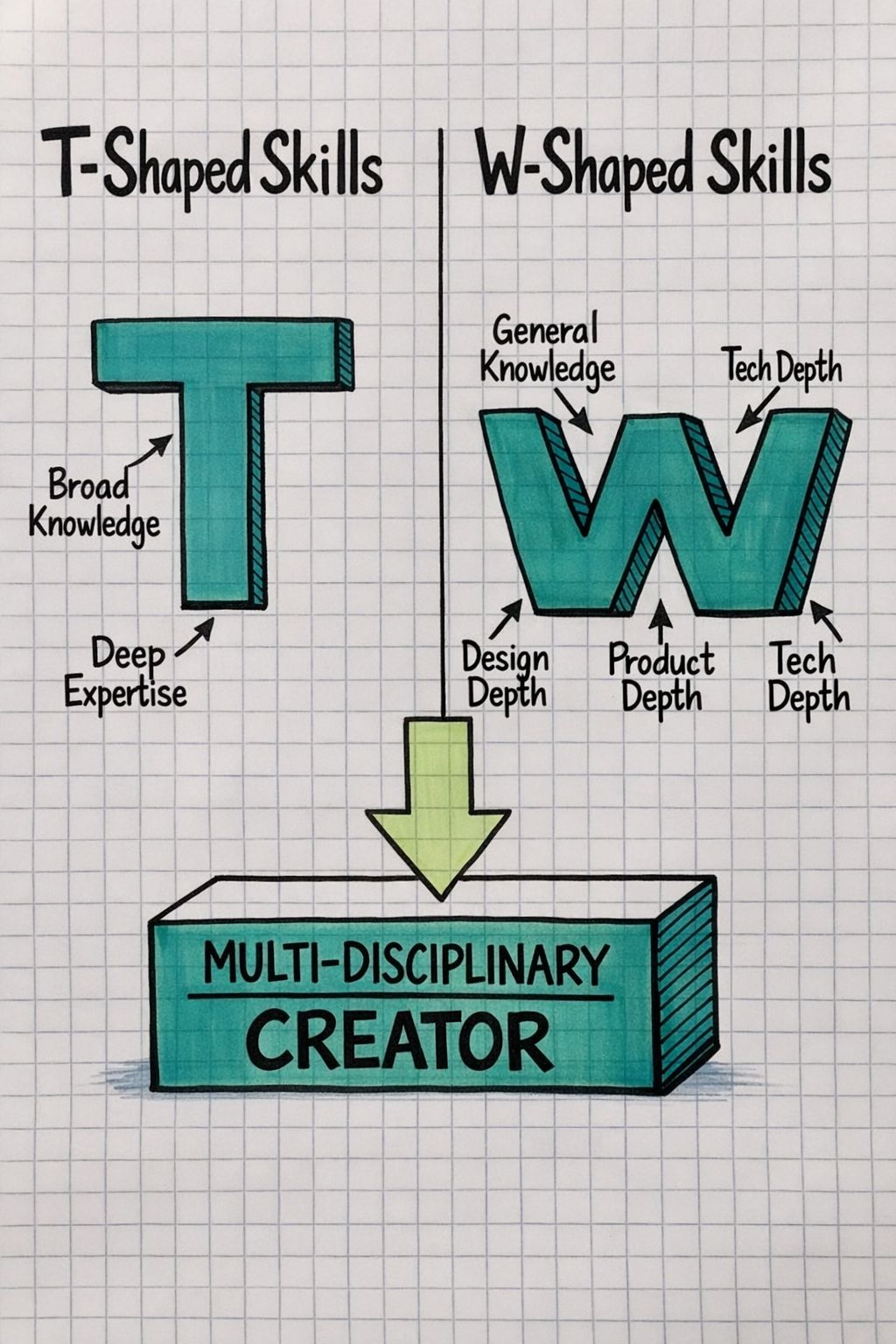

I think of this as being W (or weirdo) shaped, rather than T-shaped. In other words, a person with good general knowledge and depth of knowledge in more than one area will excel now and in the future. In a sense, being “weird” is akin to being indispensable and non-fungible.

In fact, Lenny asked this very thing about designers, saying that while designers can learn to become product managers and engineers, design skills are harder to learn for engineers and product managers.

— Justin Lokitz

Design Deep Dive

Why Being W-Shaped Is Design’s Superpower in the Age of AI

As noted above, for the last twenty years, product teams have been built around specializations, like product management (which is really akin to business strategy), software engineering, and design. Much like Henry Ford’s concept of an assembly line, specializing in different parts of the process helps to ensure that they’re expertly handled.

Of course, there’s a real cost to this way of working as well…especially when it comes to software, which is NOT the same as assembling a car using the same parts over and over. That cost is coordination…months of handoffs, translation, negotiation, and rework.

This structure for software creation made sense when tools were brittle, and expertise was locked behind years of training. With the advent of generative AI, including vibe coding, it makes far less sense now.

In my recent interview with Sid Vanchinathan, he described how these roles are collapsing into what he calls the digital product creator: someone who can move fluidly from idea to interface to working system with minimal mediation. His argument is blunt. Product teams are about to get much smaller, not because work is disappearing, but because the work is being recomposed.

And…as I noted above, just this week, Marc Andreessen, the well-known venture capitalist and technologist, made a strikingly similar point on Lenny’s Podcast. Asked directly about the future of product managers, designers, and engineers, Andreessen described what he called a “Mexican standoff” between the three roles.

“Every coder now believes they can also be a product manager and a designer because they have AI,” he said. “Every product manager thinks they can be a coder and a designer. And then every designer knows they can be a product manager and a coder. They’re actually all kind of correct.”

What matters is what happens next.

The End of the T-Shape

For years, the dominant career advice in design and tech was to become T-shaped: broad general knowledge with depth in one core discipline. In many respects, academia is designed to teach the same. Zooming out (and looking backwards), that model is optimized for large teams and stable boundaries between roles.

AI completely changes this math! Andreessen puts it this way…

“The additive effect of being good at two things is more than double. The additive effect of being good at three things is more than triple. You become a super relevant specialist in the combination of the domains.”

This is not a call to become mediocre at everything. It’s quite the opposite. It’s an argument that depth in multiple domains compounds, especially when AI handles large portions of execution.

That’s why a better metaphor now is not T-shaped, but W-shaped…or, what I like to call weird (or weirdos ;-). This is all about strong general judgment, plus deep capability in more than one vertical. Design and product. Design and engineering. Design and strategy.

The “weird” part of the W is where leverage lives.

Why Design Adapts Faster Than Other Disciplines

Lenny pressed Andreessen on a sensitive point. If everyone can now code, design, and manage products with AI, what actually becomes scarce?

The implication was clear even when unstated. Unlike product strategy and coding, design skills are harder to brute-force. Sure, a big part of design is synthesizing customer input, which anyone with AI can do now. But…as discussed in earlier articles, skills like taste (if one can even call taste a skill) are much harder to learn.

Though any AI can construction and interface, this is the wrong way to think about design. Design is…framing problems, making tradeoffs visible, sensing when something is off before metrics catch up, and shaping systems that people can actually use. Those are judgment skills, not syntax skills. Taste, my friends, is what designers acquire over years of making decisions and backing those decisions up with “why”.

Sid makes a similar point in his writing and interviews. The designer who learns to ship code or define a roadmap doesn’t stop being a designer. They become dangerous in the best sense. They collapse feedback loops. They stop waiting for permission. They reduce the translation loss that kills speed and quality in complex systems.

Engineers can learn design tools. Product managers can learn UX patterns. But… design judgment is built through exposure, critique, and taste. It does not download cleanly.

That’s why designers who expand outward tend to gain leverage faster than non-designers trying to bolt design on.

AI Rewards Boundary-Crossers

One of the most misunderstood effects of AI is that it doesn’t eliminate roles so much as it dissolves the seams between them.

Andreessen reframes the entire jobs debate around tasks, not titles.

“Everybody wants to talk about job loss,” he says, “but really what you want to look at is task loss. The job persists longer than the individual tasks.”

When tasks dissolve, the people who can recombine them matter more, not less.

This is exactly what Sid is pointing at with the digital product creator. When a single person can reason about the user, sketch the interface, prompt or generate the code, and ship a working system, the economic center of gravity shifts. Coordination overhead collapses. Small teams outperform large ones. Individual judgment becomes the bottleneck. AI doesn’t replace designers here. It amplifies them.

Indispensable and Non-Fungible

Andreessen offers a final piece of advice that feels almost obvious and yet under-acted on: “People who really want to improve themselves and develop their careers should be spending every spare hour… talking to AI being like, ‘All right, train me up.’”

This is not about replacing their craft, but stretching it sideways…or maybe weird-ways.

A W-shaped designer is not a unicorn. They are someone who understands users deeply, can reason about systems, and can now execute across boundaries without waiting. That combination is hard to replace, hard to outsource, and hard to automate away.

In a world of smaller teams, faster cycles, and AI-accelerated execution, that profile is not a nice-to-have. It’s the new core.

If you think about it: design’s superpower was NEVER just aesthetics. It was synthesis.

AI simply removes the excuses for not using it. And…as Archimedes once said…

“Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.”

Subscribe to Design Shift for more conversations that help creative professionals grow into strategic leaders.

What did you think of this week's issue?