Last week’s issue explored how taste works beneath the surface…how exposure, reflection, and synthesis sharpen your internal compass until you can see structure where others see style. With that single 1,800-ish word article, I received a ton of great questions and feedback. Thank you for that!

Many of you asked the same follow-up: once your taste sharpens, what do you do with it? How does that sensibility turn into judgment that the rest of the team can actually use?

So…rather than jump to an entirely new design subject this week, I figured I would double down on the thread, but with a twist. Because taste on its own doesn’t create leverage. Judgment does. And…judgment comes from learning how to articulate your interior reasoning in a way others can understand, challenge, and eventually share.

That’s where critique enters the story! Not the brittle, defensive version so many organizations I have encountered learned to avoid, but the older, more generous practice of studying work together. Critique is the bridge between personal taste and collective judgment. And if we want teams to develop a shared sense of what “should exist,” we MUST (x10) revive critique as a disciplined, structured, psychologically-safe ritual again.

Let’s take that step, and let’s ground it in Ridd’s definition: taste is understanding what you think should exist, and being able to repeatedly answer why. Read on for more…

— Justin Lokitz

Design Deep Dive

Reviving Critique: The Missing Link Between Taste and Better Decisions

Last week, we explored taste as something earned through attention and time…and asking a “why” a lot. You immerse yourself in references. You notice what moves you. You sit with the feeling long enough for its structure to surface. Eventually, you stop saying “I like this” and start understanding why it works (at least for you).

But if taste stays inside your own head, it’s inert. It shapes your opinions, not your team’s understanding. The moment you begin explaining why (why this pattern holds together, why that choice breaks the narrative, why a concept feels thin or solid), you cross a threshold. You move from intuition to judgment.

Ridd’s framing (i.e., “taste is understanding what you think should exist, and then being able to repeatedly answer why”) is useful because it centers taste as intention. Taste is your sense of what should exist. Judgment is your ability to reveal the reasoning behind it.

In my experience, the real challenge here is that most teams have lost the shared practice that used to make this possible: critique. In fact, I’ll go one step further and state that I have heard dozens of recent accounts from design managers at tech companies where not only is the practice of critique (mostly) lost, but for many designers, critique feels like a personal affront.

If the central human tools that we bring to the table alongside AI counterparts are creativity, taste, and judgment, we MUST (10x) incorporate embrace critique as a foundation for making better decisions (for other humans)...together!

One of MANY critiques (or crits) taking place at California College of the Arts

Critique, in its original form, was a communal act of seeing rather than a performance or a search for consensus. People offered their perceptions not as judgments to win an argument, but as lenses, or ways of revealing something others might have missed. Good critique, as taught by MANY art, design, and architecture schools, like California College of the Arts (CCA), was (and is) about making the reasoning behind the work visible, so everyone could understand its integrity or instability.

Over time, critique (especially in the corporate realm) has become something else. Too sharp. Too personal. Too vulnerable. Many organizations and design leaders have quietly abandoned it. Decisions have moved into private conversations or senior reviews…often too late and too disconnected to do anything about the work. Designers have learned to “sell” work through beautifully designed pitch decks rather than study it. And as critique has died, so has a key mechanism for developing shared judgment.

But critique is exactly the environment where the idea of “repeatedly answering why” becomes a collective practice rather than an individual one. Every time you answer why, you expose the scaffolding under your taste. You let people see your structure of thinking. And when others do the same, judgment becomes distributed and collective rather than centralized and deeply personal.

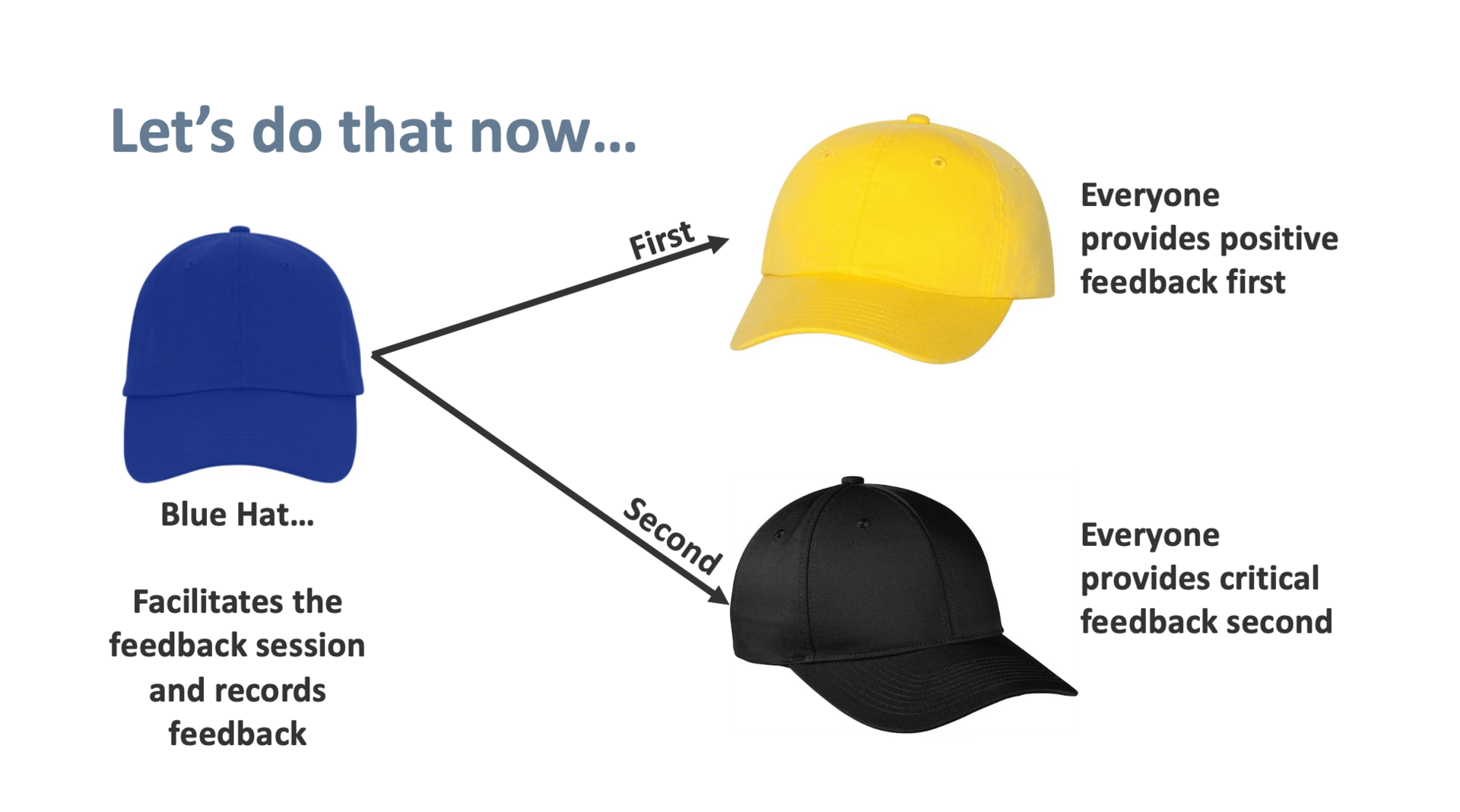

The trick is giving critique enough structure that it stays stable and safe. This is where my absolute FAVORITE and most used critique techniques, De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats, fits beautifully. If you have not read this seminal work, simply titled Six Thinking Hats, which is also a scant 192 pages (in large type), honestly, you should…it’s a must.

De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats

The gist is this: most critique collapses because it conflates modes of thinking. Someone is exploring possibilities, while someone else is flagging risks, while someone else is evaluating evidence, while someone else is reacting emotionally. When everything happens at once, people start defending rather than seeing. This is where designers from all disciplines back away, offended and entrenched in their own point of view, rather than lean in.

In many ways, De Bono addresses this by creating a shared rhythm (called “parallel thinking”): everyone looks through the same hat at the same time. It’s simple, but it restores coherence and psychological safety. For design leaders trying to translate taste into shared judgment, this technique provides a way for teams to examine work with intention rather than instinct alone.

In fact, the handful of design leaders I know who have incorporated De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats into their own team’s practices have described to me how energized and (re-)motivated their designers are.

I teach this VERY same thing to ALL of my students at the DMBA

As a simple introduction to how this works, each hat, which is just a metaphor for a way of thinking and providing feedback, brings something essential to the practice of judgment via shared critique:

The White Hat pulls the conversation back to facts and evidence. It prevents taste from drifting into unfounded claims.

The Red Hat legitimizes intuition—your immediate sense of resonance or discomfort—without needing a full explanation yet.

The Black Hat invites critique of structure, coherence, and risk. This is where taste often first shows up as a signal.

The Yellow Hat asks what’s working and why—forcing the articulation of strengths instead of only weaknesses.

The Green Hat expands possibilities and variation, helping the team explore what could exist rather than what currently does.

The Blue Hat manages the process, ensuring the conversation doesn’t collapse into a pile of competing instincts.

If you read last week’s piece through the lens of the hats, you can see how they align with taste itself.

Exposure creates the raw material the Red and Yellow Hats draw from.

Reflection is a Blue Hat discipline…stepping back to ask what’s actually going on.

Synthesis is the Black and White Hats working together…naming the underlying structure with clarity.

Together, they create a language any team can use to examine not just the work, but the thinking behind the work. The hats keep the conversation from relying on charisma, hierarchy, beautifully designed pitch decks, or whoever “has the best eye.” They turn critique into a shared method.

And…when critique becomes shared, the reasoning behind taste becomes shared as well.

This is how judgment spreads!

You begin by articulating why something feels off.

Someone else adds what the data reveals.

Someone else names a structural tension in the narrative.

Someone else surfaces a promising direction worth exploring further.

The team sees the work through multiple hats, multiple lenses. And…slowly, the room builds a common understanding of what strong work looks like.

Not because you, the design leader, declared it, but because you studied it together…as a team.

This is the heart of judgment: a group of people learning how to think and make important decisions as a team, even when everyone’s natural inclination may show up differently.

What’s more, as AI multiplies the number of plausible directions a team can explore, critique becomes even more important. When there are twenty variations developed overnight instead of two (as I discussed with Sid Vanchinathan), you need a shared way of separating structural strength from surface novelty. This is EXACTLY where De Bono’s hats shine. They help the team slow down, see clearly, and develop the same mental muscles that shape your taste.

Taste may begin with you, but judgment only matters when it becomes ours.

And critique—specifically the kind that is structured, generous, repeated—is the mechanism that turns solitary taste into collective clarity. After all, feedback is a gift.

If you’re at all interested in discussing how to train your team in the art of using De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats for critique, by all means, feel free to reply to this email. As you can probably tell, I LOVE this framework and believe it can help any team excel together.

Subscribe to Design Shift for more conversations that help creative professionals grow into strategic leaders.

This newsletter you couldn’t wait to open? It runs on beehiiv — the absolute best platform for email newsletters.

Our editor makes your content look like Picasso in the inbox. Your website? Beautiful and ready to capture subscribers on day one.

And when it’s time to monetize, you don’t need to duct-tape a dozen tools together. Paid subscriptions, referrals, and a (super easy-to-use) global ad network — it’s all built in.

beehiiv isn’t just the best choice. It’s the only choice that makes sense.

What did you think of this week's issue?