Though I’ve been thinking a lot about taste lately, much of the idea of taste (at least in my mind) comes from two things: decision making…and (actually) making things.

Like many people who’ve worked in and around tech, I’ve spent the entirety of my career around people who make things for a living. Designers, founders, engineers, and builders of all kinds. In all of this, one pattern keeps repeating: judgment comes from doing the work, not just talking about it. Yes, you can make decisions. But And…the most sound decisions almost always come from people who are intimately familiar with doing the work. Making digital and/or physical things.

That said, AI has radically compressed the distance between intent and output, which is extremely useful and even magic at times. And…it’s also dangerous.

Right now, many designers and would-be designers are quietly replacing practice with prompting and calling it progress. The work looks finished while the learning is thinner.

Hence, it’s high time we also defend simply making things, as humans. Not as nostalgia or craft romanticism, but as the only reliable way designers develop judgment, credibility, and leadership when AI is everywhere.

Read on for more…

— Justin Lokitz

Design Deep Dive

Prompting Is Not Practice: What Designers Lose When They Stop Making

Making is where designers of all kinds encounter reality. That’s the part no tool can shortcut. Full stop!

When you build something, even something small or rough, it pushes back, sometimes physically, sometimes digitally. Materials behave unexpectedly. Systems reveal edge cases. Users Customers misunderstand what felt obvious in your head when you made the thing, yet now it feels superfluous. Those moments are not inefficiencies. They are the training data for judgment. They teach all of us what matters, what holds up, and what breaks under pressure.

Courtesy of IxDF - The Interaction Design Foundation

Though I am a huge advocate of employing AI as a set of materials and/or new tools for collaboration, I also feel that when we boil AI down to the act of prompting, the resistance and validation (or invalidation) we seek is (mostly) removed.

You ask, you receive, you tweak, you regenerate. The loop feels productive, but it’s fundamentally different. You are selecting, not deciding. You are reacting to outputs rather than committing to a direction and living with its consequences…or learning quickly how to pivot based on them. Over time, I believe that erodes a designer’s ability to say “this is the right move, and here’s why.”

There’s emerging research that backs this up. Studies on AI-augmented creativity show that generative tools are helpful early on. They expand the search space and reduce cognitive load. But…they do not replace the deeper learning that comes from wrestling with problems directly. In architectural and design education, researchers found that AI-supported exploration and engagement, but meaningful outcomes still depended on human framing, constraint-setting, and interpretation. The thinking didn’t disappear. It just became more important (x10).

This distinction matters because design judgment is not pattern recognition alone. It’s sequencing, tradeoffs, and consequences. We all learn it by doing things in the wrong order and paying for it through critical feedback. We learn it by overbuilding, underbuilding, and correcting course. In many respects, AI smooths those rough edges, which is useful in production and risky in practice.

I see this show up most clearly in critique. When work is made, critique has something to grab onto. You can trace decisions and ask why this constraint was honored and that one ignored. You can disagree productively. When work is generated, critique collapses into preference. “I like this one better.” “This feels cleaner.” The reasoning trail is hidden, so shared judgment never forms.

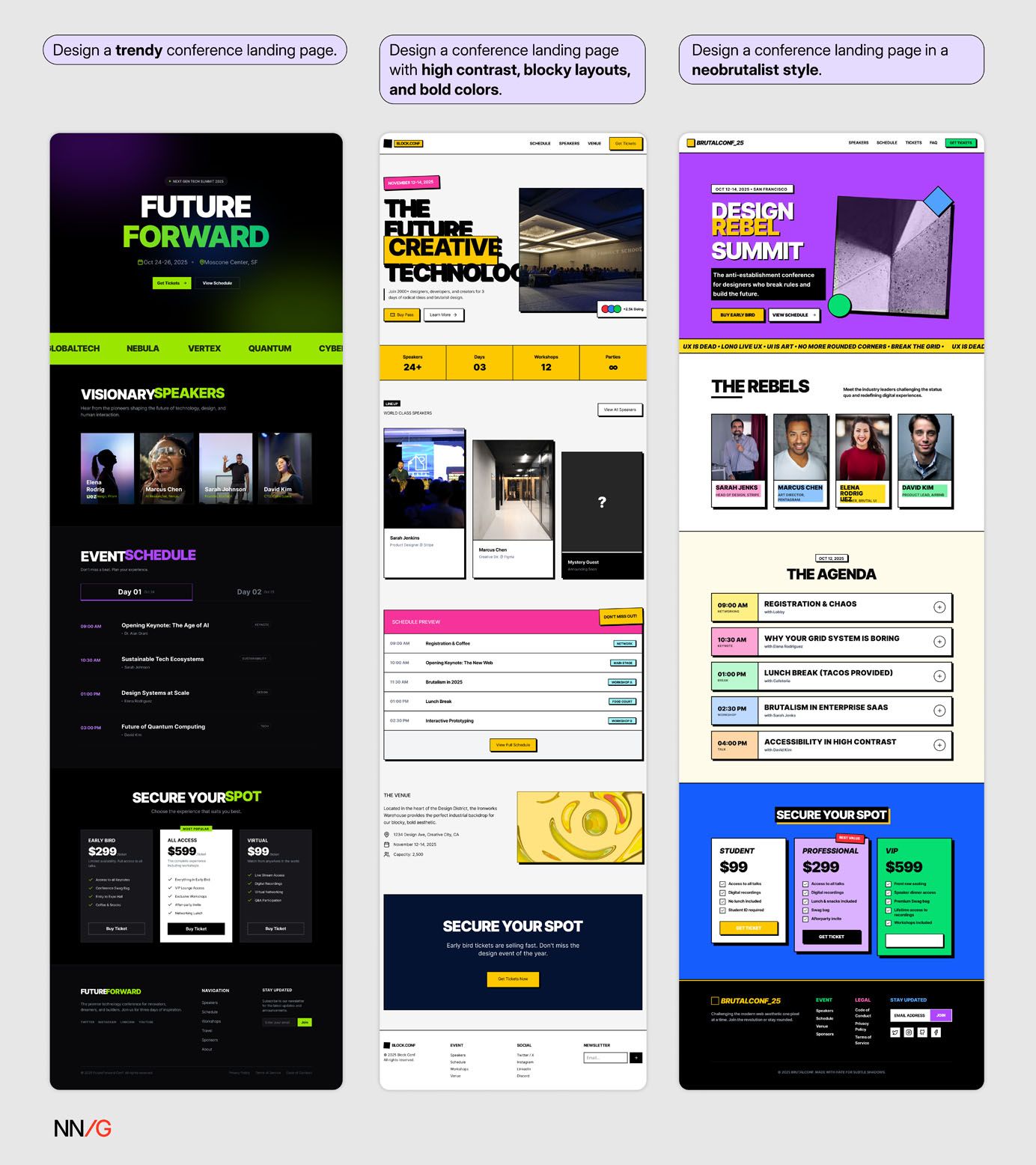

Nielsen Norman Group recently pointed this out in the context of AI prototyping. Vague prompts lead to inconsistent results, and quality depends less on the tool than on the clarity of human intent. That’s the tell if I’ve ever heard/seen one! If your outcome hinges on how well you specify context and constraints, then those decisions still belong to you. In this way, prompting doesn’t remove responsibility as much as it obscures it.

What’s more, in my own experience making things with AI, I’ve found that the more cognitive and creative load I offload to AI, the weaker I become at decision making…and plain old making things. For instance, while I love creating landing pages using Lovable, I’ve found that I don’t always know what I like or don’t like about them, nor what I would do to change things.

As someone who started his freelance/design career in 1999, building 5-page static websites for small businesses, I can say in all honesty, the way I employ AI today is a dangerous game.

All that to say this: leadership is where the cost of skipping making becomes unavoidable. Designers who no longer make something struggle to earn trust across disciplines. Not because they lack ideas, but because their opinions aren’t grounded in actually having made incremental decisions. What’s more, builders understand feasibility because they’ve hit limits firsthand. They know where ambition needs support and where it needs restraint. That kind of judgment can’t be faked with vocabulary or outputs.

There’s also a quieter loss happening around taste. Taste sharpens through exposure and reflection…and it stabilizes through application. I don’t think you really know if your instincts are good until you apply them under constraint and see what survives. Without making taste tends to drift. It becomes an aesthetic preference rather than a reliable compass for action. AI can remix taste endlessly, yet it cannot validate it.

Research on human–AI co-creation keeps reinforcing the same conclusion! The strongest outcomes come from structured collaboration, where humans set direction, frame problems, and negotiate with the system…even when that system (or co-worker) is AI. As stated above, unstructured prompting underperforms. And…in this, the human role becomes more explicit.

This aligns with older ideas around critical making, which ties hands-on production to reflection and critique. The premise is simple: building things exposes assumptions that abstract thinking hides. In a world where outputs look finished by default, that exposure is more important than ever.

None of this is an argument against AI. Again, I use these tools daily. No, really. They’re powerful. They expand possibilities. They surface patterns faster than any individual can. But…they do not absolve designers of the work that actually trains judgment. If anything, they raise the bar. When tools are cheap and abundant, the differentiator becomes the quality of decisions behind them.

The real risk isn’t that AI replaces designers. It’s that designers replace practice with selection and slowly lose the muscle that made them valuable in the first place. Making is not a phase you graduate from. It’s professional hygiene. It’s how designers earn authority, build trust, and develop the judgment teams rely on when the tools stop being impressive, and the decisions start to matter. Making is how we form the “why” of a design decision.

If you care about staying relevant in the age of AI, protect making. Do the work. Touch the constraints. Own the consequences. That’s where judgment lives.

Subscribe to Design Shift for more conversations that help creative professionals grow into strategic leaders.

What did you think of this week's issue?